Reminder to Register

Orthosports Annual Orthopaedic Updates,

Saturday, 8th November, 2025

Register for Live event @UNSW CLICK HERE

Register for Webinar(live & recorded) CLICK HERE

If you have a Question that you would like answered on this monthly email please send to education@orthosports.com.au

QUESTION | HOW DO YOU DECIDE WHICH AC JOINT INJURIES NEED SURGERY?

ANSWER |

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint injuries are common in contact sports, often resulting from falls or direct trauma to the shoulder. While the deformity is seen at the AC joint the main injury is actually to the coracoclavicular ligaments. These resist superior movement while the AC joint capsule resists mainly AP displacement; and the Deltoid and Trapezius attachments provide dynamic stability.

The most common mechanism of injury is direct trauma with a fall onto the point of the shoulder (such as a rugby tackle). Indirect trauma such as falling onto an outstretched hand with transmission of force to the AC joint is far less common.

Classification

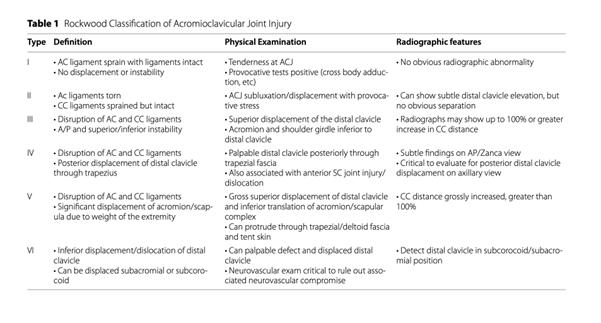

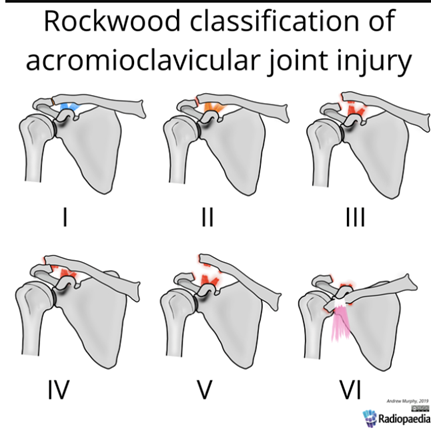

Cadenat was probably the first to document the injury in 1917 (The treatment of dislocations and fractures of the outer end of the clavicle. Int Clin 1917) and Allman and Tossy (CORR 1963 ) initially described 3 levels of joint separation. This was modified by Rockwood (1996) into 6 subtypes and this continues to be the most used classification nowadays.

Examination

Injury to the AC joint is often a relatively high energy injury and it is important to rule out injuries to the surrounding structures. This includes examination of the glenohumeral joint, sternoclavicular joint, cervical spine and ribs as well as a neurovascular examination. It is possible to injure the glenoid labrum, biceps and rotator cuff at the time of injury.

The clinical findings are usually very obvious with pain and swelling or a large lump at the AC joint. The patient will typically be unable to raise their arm above shoulder height or across their body. The tests described to diagnose this condition are: The cross-body adduction test, O’Brien’s test (AC variant), AC shear test and Paxinos test but the diagnosis is usually very obvious in anything greater than a grade I injury.

The ‘collapse sign’ is often used to decide whether to operate on type III injuries where an external rotation strength test is performed with the arm in adduction. It is considered positive if the clavicle rides up and over the acromion with the shoulder girdle moving medially or ‘collapsing’ under the clavicle, often indicating greater AP instability as well as superior/inferior instability.

Imaging

The diagnosis is made both clinically and from plain radiographs. It is important to obtain an axillary lateral to see if the clavicle has moved posteriorly as well as superiorly. The Zanca view is designed to look specifically at the AC joint and may need to be specifically requested (Most good imaging centres will do this automatically if you write AC joint injury in the clinical notes of the xray request form). Stress views are rarely done these days as surgery is almost never indicated if the joint is not separated with the arm at rest. MRI scanning can be used in cases where injury to other structures around the shoulder is suspected or to evaluate the coracoid for a fracture as this may affect treatment options.

Treatment

Non Operative Management

Types I–III is symptom based, not time based. The numbers below are a general guide only.

Phase 1: Acute (0–2 weeks)

Sling for comfort (Type I: ~3–5 days; Type II/III: ~10–14 days).

Ice, anti-inflammatories, pain management.

Early pendulum exercises, scapular setting, gentle AROM within pain limits. No specific restrictions on the use of the arm.

Phase 2: Subacute (2–6 weeks)

Progress to full AROM by week 4–6.

Sometimes a cortisone injection is required for pain relief

Initiate isometric rotator cuff strengthening, scapular stabilization, and closed-chain drills.

Avoid cross-body loading and overhead lifting initially if these cause pain

Phase 3: Advanced (6–10+ weeks)

Eccentric and plyometric training (e.g., wall dribbles, perturbation training).

Progressive strength and power work—bench press, push-ups. Avoid military press and lateral raises >60 degrees until completely symptom free.

Reintroduce sport-specific drills (passing, tackling technique, throwing).

A horse shoe shaped pad can be taped to the acromion to relieve direct pressure on the distal clavicle.

Type I–II: RTP 2–4 weeks (non-contact sports), 4–6 weeks (contact).

Type III: RTP varies from 6–12 weeks depending on:

Symptom resolution, Strength symmetry, Sport-specific loading tolerance.

Criteria-based RTP should include:

No AC joint tenderness or instability,

Full pain-free ROM and strength,

Full contact simulation if applicable.

The principles of the operation are to reduce the AC joint and reconstruct the coracoclavicular ligaments. There are many different operations that achieve the same outcome but each has different advantages and risks.

My approach is to perform one operation with a low risk profile that does not require a second operation to remove hardware before the person can return to sport. The described operations to treat this condition vary from a simple dacron graft reconstruction and AC joint repair to drill holes and metal buttons, use of tendon grafts and insertion of a hook plate which needs to be removed with another operation 6-12 weeks later. My technique is described in the handout in the link at the bottom of this page.

Treatment of chronic injuries usually requires the addition of fresh biology such as tendon grafts to achieve healing.

A sling is used for 6 weeks to protect the repair

Weeks 0-3 Pendular exercises only

Weeks 3-6 Passive ROM, stay in sling when not exercising

Week 6 onwards Strength progression. Professional athletes usually resume contact at 8 weeks but for most patients this takes 12 weeks to be comfortable

The main indications for treatment are persistent pain with activities such as bench press, overhead lifting, or contact sports. Some patients do feel the AC joint instability. Some occupations like scaffolders and electricians who spend a lot of their work day with their hand overhead can feel scapula fatigue / pain as well. Non operative treatment is always tried first but a delayed reconstruction can still give excellent outcomes. It is often a combined procedure using a synthetic graft combined with a tendon (autograft or allograft for vertical stability) and another procedure to deal with AP stability such as a Weaver Dunne procedure, excision of the distal clavicle or other soft tissue reconstruction to stabilise the AC joint.

Conclusion

Grade I and II injuries are best treated non operatively.

Early referral for higher grades is needed.

Most Grade III injuries can be treated without surgery but there are certain cases where surgery is beneficial.

Grade IV-VI injuries do best with early surgery

Functional recovery from the surgery is generally very good

PLEASE CLICK HERE TO READ FURTHER