Welcome to Question for Physiotherapists, March, 2022

This month Dr Michael Goldberg discusses the Hypermobile Lateral Meniscus.

Please feel free to send your questions to education@orthosports.com.au

Answer: It sounds like this patient may have a relatively uncommon condition known as a hypermobile lateral meniscus.

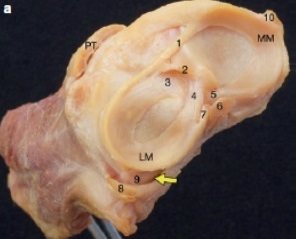

The condition is not widely known, and as such, is often not considered as a diagnosis for knee locking. Normally, the lateral meniscus is relatively more mobile than the medial meniscus. It has a number of attachments to the posterior knee which prevents subluxation of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus into the knee joint. These include the meniscofibular ligament (attaching the lateral meniscus to the fibula), popliteomeniscal fascicles (attaching the lateral meniscus to the popliteus tendon) and the anterior and posterior meniscofemoral ligaments (see figure 1). The pathophysiology of hypermobile lateral meniscus is thought to be related to either a congenital deficiency, or a traumatic injury to these ligamentous attachments. Subsequently, the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus becomes hypermobile, and is able to sublux into the knee joint.

Cadaveric Specimen of left knee joint:

MM: medial meniscus, LM lateral meniscus, PT patellar tendon.

1. Transverse ligament. 2. Tibial attachment of anterior cruciate ligament. 3. Anterior root of lateral meniscus. 4. Posterior root of lateral meniscus. 5. Posterior root of medial meniscus. 6. Posterior cruciate ligament. 7. Anterior meniscofemoral ligament. 8. Popliteus tendon. 9. Meniscofibular ligament. 10. Medial collateral ligament.

Hiatus popliteus – marked with the yellow arrow.

Patient history is key for diagnosing this condition, as examination and investigations are usually normal. Patients with this condition present mostly with mechanical symptoms of the knee. The most common symptom is locking of the knee with hyperflexion, or the figure-of-4 position (when the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus is most likely to sublux into the knee joint). If the episodes occur frequently enough, patients may have worked out a specific way to unlock their knee. Less common symptoms include catching, clicking or pain without mechanical symptoms. Most do not have a history of knee trauma. Duration of symptoms may range from months to over 10 years. (A 32 year old patient I recently saw with this condition described intermittent locking since she was 8!). The condition may occur bilaterally. It may affect both paediatric and adult patients.

MRI scans most commonly demonstrate a normal lateral meniscus. The only way to identify the condition on MRI, is if the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus is locked in the knee joint at the time of MRI, which may be mistaken for a displaced bucket-handle tear.

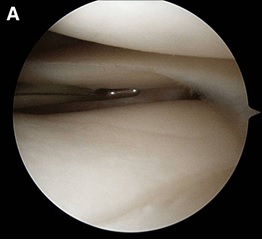

The diagnosis is confirmed arthroscopically, by the ability to translate the entire posterior horn of the lateral meniscus anterior to the midpoint of the tibial articular surface, using an arthroscopic probe (see figure 2B). Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment is to stabilise the meniscus by repairing it to the posterior capsule of the knee.

Further reading: Van Steyn, M.O., Mariscalco, M.W., Pedroza, A.D. et al. The hypermobile lateral meniscus: a retrospective review of presentation, imaging, treatment, and results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24, 1555–1559 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3497-0

237824306_Popliteomeniscal_Fascicle_Tear_Diagnosis_

and_Operative_Technique