Welcome to Orthosports Question for Physiotherapists August 2024. This month Dr Leigh Golding discusses side strain from a sporting injury.

REMINDER: SAVE THE DATE Orthosports Annual Orthopaedic Updates, Saturday, 9th November 2024, live @UNSW or via webinar. Registration opening soon.

If you have a Question that you would like answered on this monthly email please send to education@orthosports.com.au

QUESTION | A 23-year-old male right-handed cricket fast bowler experiences a very mild awareness in his left trunk region during the delivery phase of the bowling action during a match. During the next delivery, he feels this suddenly get worse, and he now reports significant left-sided trunk pain that is worse with trunk rotation, lateral flexion, and deep inspiration. He reports being unable to continue playing the match and presents to your clinic six days later. He is minimally symptomatic at that point; however on examination, he has some reproduction of his ‘side’ pain on resisted left-sided lateral trunk flexion. He wants to return to play on the weekend for a 20-over match but is seeking your advice on how to proceed.

Side strain is a common cricket injury. It is most often associated with cricket and baseball athletes but can also occur in sports with repetitive unilateral actions. It typically occurs acutely on the contralateral side to the dominant arm. The anatomy of the lateral trunk region affected by side strain is complex; however, the muscle most affected on imaging is the internal oblique. Other muscles that may be affected as part of the injury include the external oblique, transversus abdominis, and intercostals. Younger athletes (<25 years) tend to suffer side strains more commonly than their more experienced teammates[1].

These injuries typically present with acute pain over the anterolateral or posterolateral thoracic wall. In the early stages, coughing, sneezing, rolling over in bed, and deep inspiration are usually painful. There is often tenderness present on palpation of the rib margin at the injury site. Lateral flexion range of motion is typically reduced and limited by pain in both directions and/or a jamming or squashing symptom when moving towards the injured side. In cricket fast bowlers, pain during resisted lateral flexion towards the injured side may be seen. Isometric resisted shoulder adduction at 90 degrees abduction on the side of injury may also reproduce symptoms. Rotation and lateral flexion movements can also exacerbate the pain.

An important differential diagnosis to consider is costoiliac impingement, which may present with similar symptoms. However, costoiliac impingement typically presents in a gradual fashion. There is usually no pain on resisted tests and no pain at end-range lateral flexion towards the uninjured side (stretch), a test that is often painful in the presence of a side strain. Athletes who have experienced side strains may present later with features of costoiliac impingement. This is thought to be contributed to by the hypertrophic scar response after the initial side strain injury.

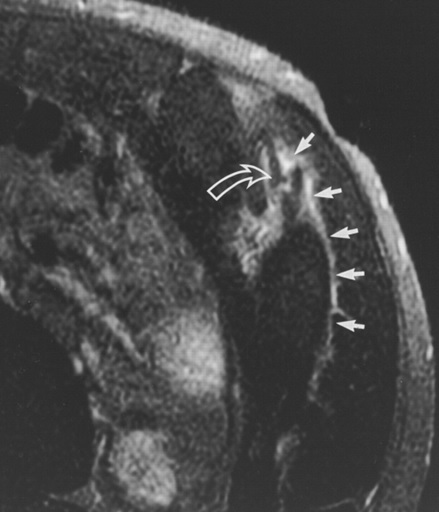

Diagnosis of a side strain can usually be made based on history and examination. MRI can be useful to confirm the diagnosis when the presentation is atypical, although the absence of an injury visualized on imaging does not exclude the diagnosis. It is important to request a dedicated sequence to assess for an internal oblique strain where side strain is suspected. Imaging providers that have experience in assessing for these in elite athletes are often able to provide dedicated sequencing protocols to assess for this injury. Return to play time has not been found to correlate well with the grading of muscle injury on imaging. However, one study showed that athletes with a muscle tear on MRI are 8 times more likely to have a return to play time exceeding 6 weeks[2]. MR imaging can also identify injury to the rib or costal cartilage, which may include bone stress or avulsion fracture and periosteal stripping, all of which are likely negative prognostic indicators.

Upon resolution of pain on deep inspiration and coughing, the athlete will generally tolerate graded strengthening and cardiovascular exercise. This commences with isometric contractions that load the chest wall muscles in neutral trunk positions to minimize the effects of pain-inhibited muscle atrophy and provide a stimulus for muscle healing. This can be progressed to concentric contractions in positions that load the area of injury, such as trunk lateral flexion away from the injured side, to further enhance the mechanotherapy effect on the healing muscle tissue. The final stage of strengthening involves the transition from concentric to eccentric and dynamic actions required for the propulsion phases of bowling and throwing. Finally, functional retraining of the specific task with graded increases in quantity and intensity is paramount prior to considering a return to competitive sport. Return to play times are highly variable but most commonly are in the range of 3 to 12 weeks, depending on clinical progression through the stages described above. Particular care and caution should be taken when progressing through the functional retraining of the return to the specific task (e.g., cricket fast bowling) as very high eccentric forces are produced here, and recurrences can often occur at this stage if the intensity of volume of this task is not well managed. Practitioners experienced in the diagnosis and management of these injuries can help construct optimal return-to-sport plans in these cases.

[1] Nealon AR, Kountouris A, Cook JL. Side strain in sport: a narrative review of pathomechanics, diagnosis, imaging and management for the clinician. J Sci Med Sport. In press. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2016.08.016.

[2] Nealon AR, Docking SI, Lucas PE, Connell DA, Koh ES, Cook JL. MRI findings are associated with time to return to play in first class cricket fast bowlers with side strain in Australia and England. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(9):992-996. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2019.05.020.

[3] Connell DA, Jhamb A, James T. Side Strain: A Tear of Internal Oblique Musculature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003 Dec;181(6):1511. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.6.1811511.