This month Dr Doron Sher presents an article on a Discoid Lateral Meniscus. Please feel free to send your questions to education@orthosports.com.au

QUESTION | A patient of mine had an MRI which reported a discoid lateral meniscus. What does that mean for their knee?

ANSWER | When I was at medical school I was taught that the meniscus started off the shape of a “D” in the embryo and then with movement and loading it turned into a “C” shape. This happened because the central part of the tissue was reabsorbed.

There were a small number of people in whom the reabsorption did not happen and they were left with a “D” shaped or Discoid Meniscus. This was the subject of a paper by Smillie in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery in 1948 where he described a personal series of 29 discoid menisci. There had been a cadaver dissection description of a discoid meniscus back in 1889 by Young but it was not until one or two years before Smillie wrote his paper that any clinical case reports were described.

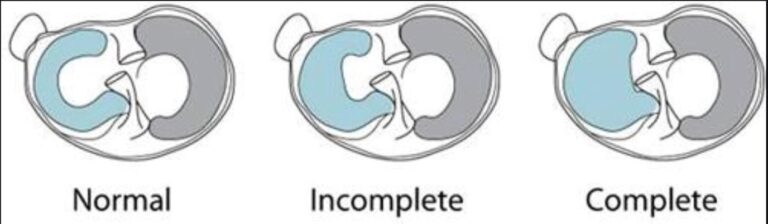

More recently the discoid meniscus has been considered a congenital anomaly rather than a developmental failure. There have been cases described of familial inheritance of this variant and also cases being found in the knees of both twins in a pair. We are not certain about the exact mechanism but it is a common condition on the lateral side of the knee (0.4-17% depending on the study) but is extremely rare on the medial side.

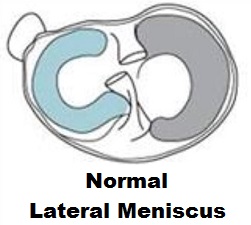

The normal lateral meniscus has a circular shape and covers nearly 70% of the lateral tibial plateau. It moves more than the medial meniscus because it is not completely attached to the joint capsule. It is firmly attached to the tibia anteriorly and posteriorly but there is no capsular attachment where the popliteus passes through the knee. A discoid meniscus generally covers the entire tibial plateau. The lateral meniscus of a right knee is shown below in green.

At birth the entire meniscus has a blood supply at birth but by 10 years of age the central third has become avascular. Unfortunately a discoid meniscus does not work as well as a shock absorber and is more likely to tear than a normal meniscus.

Classification

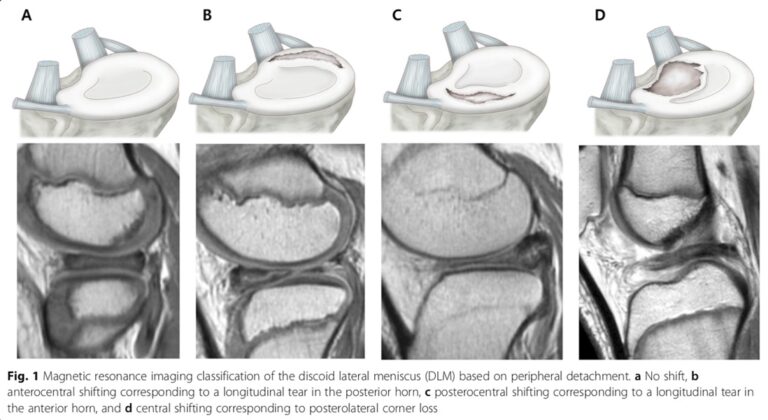

There have been several descriptions and classifications of the various types of discoid lateral menisci and their tears. This started with Smillie in 1948 (who took out the whole meniscus with open surgery) and then Watanabe in 1979 described their arthroscopic appearance. This has been modified and commented on several times since and MRI classifications have also been developed (which are more useful when it comes to surgical decision making but not very sensitive making the diagnosis).

Clinical features

The classical symptoms of a torn discoid lateral meniscus are: snapping or popping with pain, swelling, giving way, or locking (essentially the same as any meniscal tear). Adults tend to present with mechanical symptoms but younger children may just complain of snapping and inability to fully straighten the knee. There is usually a combination of: an effusion, a lack of terminal extension, anterolateral bulging at full flexion, a positive McMurray test, or joint line tenderness. These are not specific to a discoid meniscus and imaging studies are always required. It may be worthwhile imaging the other knee as well because it is commonly bilateral.

Imaging studies

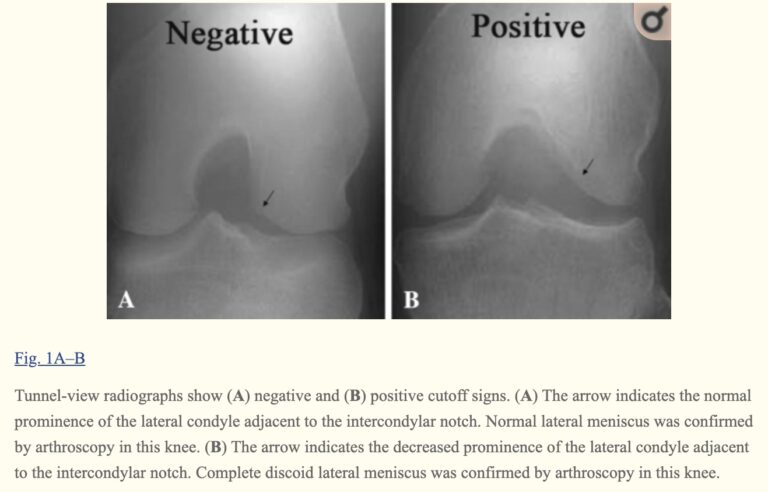

Plain radiography

Typically plain xrays are normal but there may be subtle signs such as widening of the lateral joint space, squaring of the lateral femoral condyle, cupping of the lateral tibial plateau, lateral tibial eminence hypoplasia, elevation of the fibular head, and condylar cutoff sign. Of these only the condylar cut-off sign on tunnel-view radiography has a high specificity (Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 May; 467(5): 1365–1369).

These days an MRI scan should always be performed before considering surgical intervention. Unfortunately even MRI is only about 40% sensitive at diagnosing a discoid lateral meniscus and will miss the diagnosis if the slice thickness and orientation is not correct. Clinical examination is up to 90% sensitive in experienced hands and therefore the modalities should be used together when making decisions about treatment. Ultimately an arthroscopy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis in symptomatic patients with peripheral detachment or instability, even if the tear is not visible on MRI scans.

Treatment

Decision making:

Asymptomatic, incidental finding on MRI: non-operative treatment with periodic follow-up.

Symptomatic: operative treatment – arthroscopic partial meniscectomy / meniscal repair

Subtle symptoms (eg snapping only): this will depend on the activity level of the patient and their age whether to fix immediately or to wait for significant symptoms to develop. Pain or locking require surgery.

Surgical treatment

We know that total meniscectomy results in a high risk of lateral compartment osteoarthritis and poor clinical outcomes. As with all meniscal tears, the plan should be to leave behind as much good meniscus as possible. In children and adolescents it is probably worth while at least attempting a repair which we know might not work in an adults.

If a repair is performed the patient will be kept non-weight bearing for 4 weeks and partial weight bearing for 4 weeks. They are kept straight for 2 days and then range of motion is gradually increased to 120° of knee flexion by 8 weeks. Squatting and kneeling are avoided for 6 months but straight line running might be possible at 3 months. It is not advisable for these patients ever to return to high impact sports due to the risk of re-tear of the meniscus.

Clinical outcomes

There are no great studies looking at outcomes after both partial and subtotal meniscectomy but those that are available do show reasonably favourable outcomes in the short, mid-, and long-term follow-up. They do generally show degenerative changes when sub- total meniscectomy is performed.

Poor prognostic factors:

- Older age at surgery

- Total meniscectomy

- Higher BMI (above 30kg/m2)

- Longer duration of symptoms

Conclusion

It may be difficult to differentiate a torn discoid lateral meniscus from a torn ‘normal’ lateral meniscus. A higher index of suspicion is warranted in Asian populations and often both knees are involved.

Always perform an XRay and MRI but follow your clinical suspicions if the MRI does not confirm the diagnosis.

Asymptomatic patients can be monitored and younger and more symptomatic patients are best treated with surgery. Partial meniscectomy with or without meniscal repair has shown favourable clinical outcomes and is better for the knee than subtotal or total meniscectomy.