QUESTION | My patient is a 67 year old female who has had pain during overhead activity (catching pain), going on for over 5 years. She is able to actively achieve full ROM (Including bra behind back). Her MRI shows a full thickness tear of supraspinatus tendon and a tear of the majority of the infraspinatus tendon (with a few lower infraspinatus fibers still attached). Superior subluxation of the humeral head.

I am intrigued by the patient’s symptoms and active shoulder range of motion versus her imaging.

How is she able to raise her arm up with full thickness tears of supraspinatus and the majority of the infraspinatus?

This is an excellent question and the answer is not immediately obvious. The short answer is that if 2 of the muscles are working then the shoulder can function almost normally.

Basic Anatomy and Function: As you know shoulder motion is dependent on a complex interplay of forces and moments around the glenohumeral joint. The glenohumeral joint (essentially a round ball on a flat socket) is inherently unstable. This is designed to maximise movement of the shoulder joint. The price we pay for this is the potential for instability. There is also a ‘vacuum’ within the joint capsule which stops the normal shoulder from dislocating, even with complete muscle relaxation (and after death). This vacuum is surprisingly quickly re-established by the body after the joint is surgically opened. The glenoid labrum also helps to deepen the socket but it is the rotator cuff which is responsible for keeping the joint centred with activity.

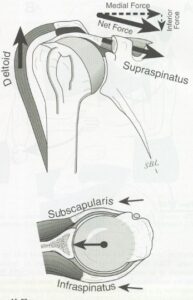

Motor Function: The deltoid muscle runs from the acromion to the lateral humerus (a relatively straight line) and moves the shoulder by pulling the humerus up (while the forces of the rotator cuff muscles effectively hold the humeral head in place) and allow the joint to rotate and the arm to move up in the air).

Forces and Moment: It makes sense that the forces and moments in the shoulder need to be balanced to keep the shoulder in place when the hand is moved above the head. The frictional force at the joint should be very small and therefore can be ignored. The anterior and posterior muscles work together to pull the humeral head into the glenoid and they work in both the coronal and axial planes. This is sometimes known as concavity compression.

In the coronal (frontal) plane, the rotator cuff force must be below (inferior to) the centre of rotation of the humerus for it to be balanced. This will biomechanically oppose the moment created by the deltoid and thus stabilize the humeral head in the glenoid. The subscapularis, infraspinatus, and teres minor are the primary depressors of the humeral head. The weight of the arm, the deltoid muscle force and the joint reaction force allow the humerus to be rotated, thereby moving the hand above the head.

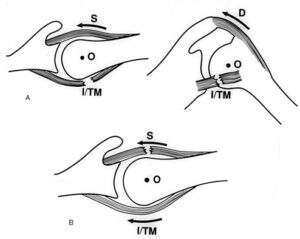

The force couple in the axial (transverse) plane must also be balanced (Subscapularis anteriorly and the Infraspinatus, and Teres minor posteriorly). If there is a balanced force pulling downwards then the supraspinatus does not need to be intact for this to happen (You would know this as muscle-balancing). With a chronic progressive tear (as is likely from the history provided) the shoulder can adapt over time.

The Tear Pattern: In the most common clinical setting when just the supraspinatus is torn, the subscapularis and posterior cuff are usually intact. As the size of the cuff tear increases it tends to extend more posteriorly (even the larger tears tend to spare the subscapularis at the front). The tear can get big enough so that the posterior cuff can no longer balance the moment created anteriorly by the subscapularis and at this point the patient will no longer be able to raise their arm above their head (a pseudoparalytic shoulder). When this happens the axial (transverse) fulcrum is lost, the coronal plane equilibrium is lost and the result is anterior-superior translation of the humeral head with attempted elevation. When this is extreme you will see anterior/superior escape of the humeral head clinically.

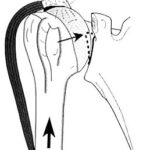

Imaging: In terms of imaging: the supraspinatus should fill the space between the humeral head and the acromion. When the supraspinatus retracts far enough the humeral head can ride up and press against the under surface of the acromion. The indicates a chronic tear and is seen as a high riding humeral head on the plain xrays. Once this happens the tear is no longer able to be repaired.

Summary: Several authors have shown that a patient with a two-tendon tear with retraction of the supraspinatus may benefit from a partial repair (ie repair of either the infraspinatus or subscapularis without repair of the supraspinatus). This is best done acutely and certainly within 3 months of any recent injury. There is also the option of performing an operation called a superior capsular reconstruction to replace the supraspinatus if you are able to get a good repair of the other 2 muscles.

In terms of your patient there must be enough of her infraspinatus still functioning to form a force couple to lift her arm in the air. If she were to extend the tear further this may no longer be possible.