Welcome to Orthosports Question for Physiotherapists August, 2022. This month Dr Doron Sher discusses a question on the glenoid track and shoulder instability.

Please send your Questions to: education@orthosports.com.au

QUESTION | WHAT DOES THE TERM GLENOID TRACK REFER TO AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT IN SHOULDER INSTABILITY?

ANSWER | The glenoid is a flat bone and the humeral head is round. Unlike the hip joint the bones do not provide inherent stability on their own. The labrum, capsule and muscles are all needed to keep the shoulder stable. These structures are not enough to hold the shoulder in joint if enough bone is missing from either side of the joint. We need to understand a few definitions to understand the concept of a glenoid track.

The presence of bone loss is a well-known risk factor for failure of shoulder stabilisation surgery. Although both humeral and glenoid-sided defects have been identified as risk factors for failure, the literature has generally treated these contributions independently. The first description of the dynamic interaction between the two was called an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. We have now taken this further and take into account both glenoid bone loss and the size of the Hill-Sachs lesion.

Definitions

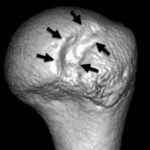

Bone loss of the humeral head is known as a Hill-Sachs lesion (HSL). This is a compression fracture of the humeral head caused by the anterior rim of the glenoid when the humeral head is dislocated anteriorly in front of the glenoid (The humeral head is softer than the glenoid). HSLs are seen after two thirds of initial dislocations and 90% of recurrent dislocations.

Bone loss of the glenoid is known as a Bony Bankart lesion. 80% of patients with anterior instability have both Hill-Sachs and glenoid bone lesions, called a ‘bipolar lesion’.

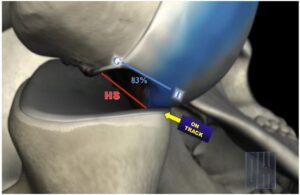

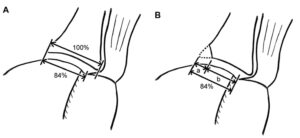

As your arm is moved away from your side the humeral head rotates and glides on the glenoid. Only a small segment of the humeral head is in contact with the glenoid at any one time. The pathway defined by this contact between the humeral head and the glenoid is called the ‘glenoid track’. The width of the glenoid track (defined as the distance between the medial margin of the glenoid track and the medial margin of the footprint of the rotator cuff) is about 84% of the glenoid width.

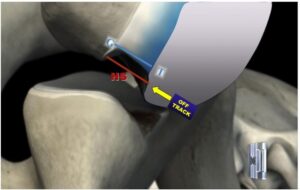

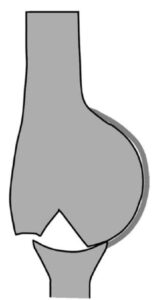

The term engagement refers to when the Hill Sachs lesion slips off the edge of the glenoid and

the humeral head dislocates from the glenoid.

remaining in contact with the glenoid despite

having some bone loss on the humeral head.

dislocated because the blue area slips off

the front of the glenoid.

If the HSL stays on the glenoid track (known as an on-track lesion) it does not engage (the humeral head does not slip off the glenoid) and therefore the shoulder does not dislocate.

On the other hand, a HSL, which is out of the glenoid track (off-track lesion), has a risk of engagement and dislocation.

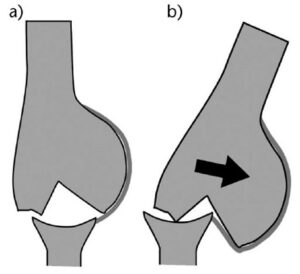

the glenoid track (between R and G) meaning a stable or on track lesion

If there is less glenoid bone then the track available for the humeral head to follow is smaller. This requires an adjustment of the way the glenoid track is calculated (see below).

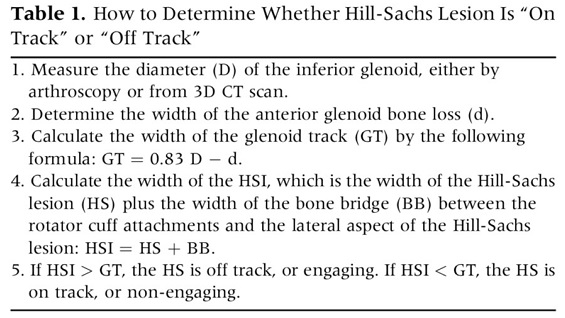

Calculations

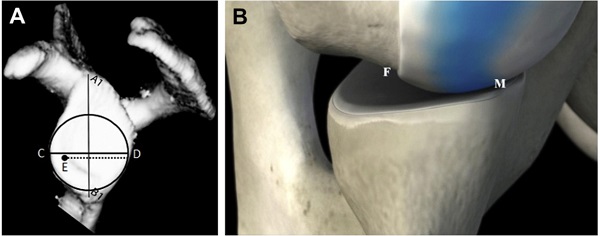

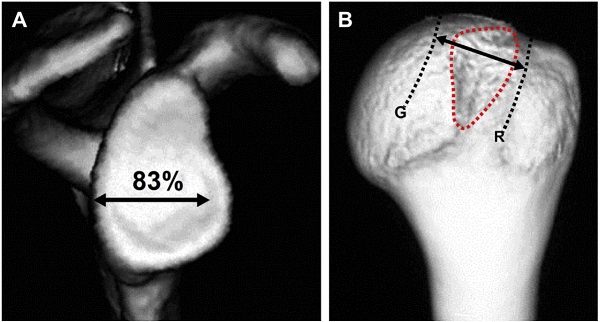

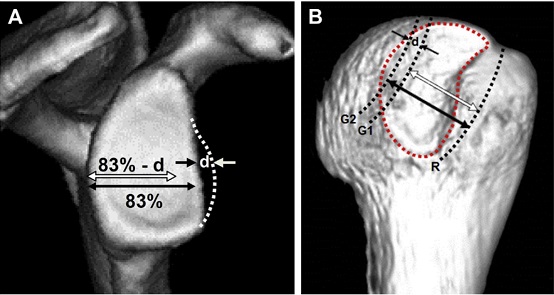

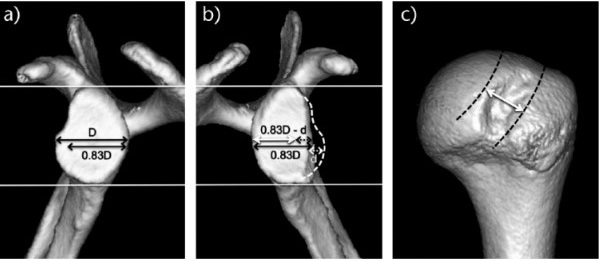

At this point things become a little more tedious because the actual calculation requires measurements and then some simple mathematical calculations. Currently the most accurate measurements are made from 3D CT scans. MRI scanning is catching up but is not as good for visualising bone loss as CT scanning is. The concept is a little easier to understand by going through the images below but: When there is no glenoid defect, the width of the glenoid track is 83% of the glenoid width. When there is a bony defect at the anterior rim of the glenoid, the defect width should be subtracted from the 83% length to obtain a true width of the glenoid track.

If the medial margin of a Hill-Sachs lesion is more medial than the glenoid track, standard stabilization procedures such as Bankart repair are unlikely to restore the shoulder stability.

Imaging

The actual imaging used is very important. You must have an ‘en face’ view of the glenoid which means you are looking directly at the glenoid on a 3D reconstruction image. This allows measurement of the glenoid width by several methods, all of which work fairly well. The other view required is posterior view of the humeral head on a 3D CT as well.

How to calculate glenoid track

1.Measure the glenoid: The first measurement to do is that of the glenoid {D} (either using the other shoulder from the CT scan or using a ‘best fit’ method which allows you to estimate it using a circle). You then calculate 83% of that number.

2. Subtract the defect if present: If there is a bony defect of the glenoid, the defect width ‘d’ needs to be subtracted from the 84% value (0.84D) to obtain the true width of the glenoid track (0.83D – d).

3.Measure the humeral head: Apply this width (0.83D – d) to the posterior view of the humeral head.

4.Decide if ‘on’ or ‘off’ track

Outcome options

If the medial margin of the HSL stays within the glenoid track, there is no risk that this HSL engages with the anterior rim of the glenoid.

If the HSL extends more medially over the medial margin of the glenoid track, there is a risk of engagement.

These used to be called ‘non-engaging HSL’ and ‘engaging HSL’ but this has been replaced by the concept of on or off track.

Treatment

Tightening the anterior soft-tissue structures limits external rotation and horizontal extension, making the glenoid track shift medially and superiorly. This shift covers the entire Hill-Sachs lesion and thus prevents engagement of the lesions (that is why an arthroscopic stabilisation is still the most common operation performed).

For off-track lesions, bone transfer surgery is most commonly performed (although this operation has a higher complication rate and creates problems in the future if the patient needs a shoulder replacement). In some situations an open capsular shift or adding a remplissage to the operation may be used, depending upon the glenoid defect size and the risk of recurrence (such as involvement in collision sports).

In the rare situation that there is significant glenoid bone loss and a large Hill Sachs lesion treatment of both lesions might be required.

Conclusion

Measurement of the glenoid track helps guide treatment of the unstable shoulder combined with several other factors. Using this measurement is helpful to reduce the number of bone transfer operations performed for shoulder instability to optimise patient outcomes.

To view Dr Sher’s video on Shoulder Instability please CLICK HERE

References:

https://eor.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/eor/2/8/2058-5241.2.170007.xml

DOI References:

10.2106/JBJS.15.01099

10.1016/j.jse.2006.12.012

10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.004