Welcome to Orthosports Question for Physiotherapists May, 2022. This month Dr Doron Sher discusses a question on treatment options for an OCD Lesion.

Save the Date: Saturday, 12 November, 2022 Annual Orthopaedic Updates @UNSW and via webinar.

Please send your Questions to: education@orthosports.com.au

ANSWER | Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee predominantly affects teenagers and people in their early 20’s. Many of these patients are involved in running sports and this condition can have a dramatic impact on them. OCD can lead to pain, swelling, mechanical symptoms and is the most common cause of a loose body in the knee in adolescents. Clinical findings can be subtle so diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion with limited range of motion sometimes the only clinical sign. Most patients provide a history of trauma as their reason for their presentation but this is usually minor and probably not relevant. In some patients the affected femoral condyle is tender to palpation. Some patients walk with the leg externally rotated in order to avoid contact of the lesion (on the medial femoral condyle) with the tibial plateau but most do not.

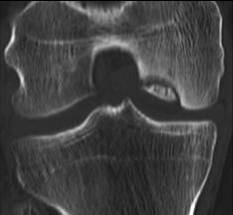

The diagnosis is made on xray but MRI has a key role in determining the stability of the lesion. Conservative management is the mainstay of treatment for stable lesions. The majority of patients respond to conservative treatment but those with unstable lesions require arthroscopic (or open) management. Unfortunately the affected knee may progress to degenerative arthritis while the patient is still young.

The etiology of OCD remains unknown despite several theories which have been proposed. These include genetics (family history), repetitive micro-trauma, growth disorders, and ischaemia. The characteristic finding of OCD is a focal area of subchondral bone that undergoes necrosis. The true incidence is unknown but is higher in males than females. OCD can involve other joints including the shoulder, elbow, hip, and ankle, but the knee is the most commonly affected. The natural history of OCD of the knee remains unclear and knowing which lesions will heal and which will not heal remains a challenge. High quality studies that report data separately for adults and children are rare and many of the publications dealing with OCD of the knee are only level IV evidence (case series).

Treatment is aimed at pain relief, improvement of knee function and prevention of arthritis. Nonsurgical treatment presents a challenge because it is difficult to predict which stable juvenile OCD lesions will heal. In the early stages arthroscopic surgery can be very effective but open surgery is still sometimes required.

OCD refers to a focal area of subchondral bone that undergoes necrosis. The overlying cartilage remains intact to variable degrees, receiving nourishment from the synovial fluid. As the necrotic bone is resorbed, the cartilage loses its supporting structure and the fragment can displace into the joint. There are two main types of OCD: the adult form, which occurs after the physis closes; and the juvenile form, which occurs in patients with an open epiphyseal plate (some people believe that the adult form is undiagnosed persistent juvenile OCD).

The knee is involved about 75 percent of the time. The lateral (mainly nonweight-bearing) part of the medial femoral condyle is the location in 85 percent of cases of OCD of the knee. OCD should be ruled out in the contralateral joint because 20 to 30 percent of cases are bilateral. Multiple lesions are rare but possible. Less frequent locations include the patella, femoral head, glenoid of the scapula, tibial plateau, head of the talus and vertebrae. Capitellar lesions of the humerus are common in adolescent baseball pitchers and gymnasts but while they look the same are probably a different disease process.

OCD is a radiologic diagnosis. If OCD of the knee is suspected, AP, lateral, notch-view (knee in flexion) and skyline patella xrays should be ordered. AP films alone may miss a lesion on the posterior aspect of the medial femoral condyle. If a lesion is seen the contralateral knee should also be xrayed. Plain films will detect a circumscribed area of necrosis but are a poor method of assessing articular cartilage and cannot be used to determine stability. If the xrays are normal the diagnosis is almost certainly not OCD.

This is clearly seen on plain x-ray and the CT does not help in deciding stability of the Lesion. This is not a useful test for this condition.

All OCD lesions seen on xray should be staged for stability with MRI. MRI has a 97 percent sensitivity for detecting unstable lesions. Other than arthroscopy, MRI is the most accurate method for staging lesions with Stages I and II being stable. Stages III and IV are unstable lesions with the cartilage breached and synovial fluid entering between the fragment and underlying bone.

On MRI, the presence of high-signal changes on T2 images signifies the presence of fluid between the fragment and intact bone. The overlying articular cartilage can still be intact in an unstable fragment. Distinguishing between stages II and III is important in planning for surgery. If the MRI demonstrates an unstable lesion (stage III or IV) then arthroscopy should be used to check the cartilage surface.

Images above: Arthroscopic views of OCD of the Medial Femoral Condyle with lesion pinned in situ.

Management: Conservative treatment of stable lesions is the general rule but I am not aware of any prospective randomized clinical trials proving that this is the right thing to do. Prognosis worsens with age and physeal closure so ideally we want to promote resolution of the lesion before physeal closure occurs. Girls younger than 11 years of age and boys younger than 13 have an excellent chance of complete resolution. Patients over 20 years of age tend to have poorer outcomes and the likelihood of requiring surgery is increased. Unstable lesions (stages III and IV) in patients with a closed physis have a particularly poor prognosis and more aggressive intervention is indicated in older symptomatic patients. In the adult form, treatment is aimed at preserving function and preventing the development of early osteoarthritis.

Nonsurgical management:

Running and jumping sports should be avoided for six to eight weeks with the goal of activity modification being to allow symptom-free activities of daily living. Conditioning exercises and quadriceps strengthening may help and if the patient remains symptomatic a period of non weight bearing on crutches may be indicated. Immobilisation is no longer used as prolonged splinting leads to quadriceps atrophy and stiffness which may complicate the condition. Persistent symptoms in a compliant patient (or complaints of joint catching or grinding suggesting detachment and a loose body) are an indication for arthroscopy.

Surgery:

Depending on surgical findings, a loose body may be removed, a fragment excised, cartilage debrided or a lesion drilled to promote revascularization. Small fragments (<5mm) or multiple OCD defects are typically removed and the base of lesion drilled to create bleeding to encourage fibrocartilage formation. Larger fragments (>5mm) in weight bearing areas are reduced and fixed where possible. This is usually done with resorbable Kirschner wires or pins. Some form of cartilage grafting may be indicated for very large symptomatic lesions (2x2cm) and while it works very well to relieve day to day symptoms it rarely gets the patient back to competitive running sports.

Stable Edge Unstable Edge Pinned:

Following surgery, range-of-motion exercises should be initiated early. Quadriceps strengthening helps promote overall knee stability and wellbeing. Weight bearing is usually restricted for 6 weeks to allow healing of the bone. Patients should be examined at three-month intervals until symptoms resolve and imaging studies are indicated for evaluation of clinical deterioration only.

Conclusion:

OCD is a relatively rare disorder but is an important cause of joint pain in active adolescents. Xray is a simple inexpensive test which provides the diagnosis and should be performed in any adolescent complaining of problems with their knee. MRI scanning and a surgical opinion should be sought for all patients with OCD lesions even though most will be treated conservatively.

Key Points:

- Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee predominantly affects adolescent and young adult patients.

- Clinical findings are often subtle so diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and limited range of motion may be the only clinical sign

- The diagnosis is made on xray but MRI has a key role in determining the stability of the lesion

- The majority of patients respond to conservative treatment but those with unstable lesions require arthroscopic management

- A surgical opinion should be sought for all patients with OCD lesions even though most will be treated conservatively.

References: Osteochondritis Dissecans History, Pathophysiology and Current Treatment Concepts Clanton, Thomas O.; DeLee, Jesse C. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 167():50-64, July 1982